Sprache

Typ

- Buch (6)

- Wissenschaftlicher Artikel (2)

- Interview (0)

- Video (0)

- Audio (0)

- Veranstaltung (0)

- Autoreninfo (0)

Zugang

Format

Kategorien

Zeitlich

Geographisch

User account

Artificial and Other Intelligences

Barbara Basting, 04.12.2019

Facebook’s picture tumbler is currently reminding me of my first visit to China a year ago. I was impressed: so many skyscrapers, so many people, so much technology! And such wonderful noodle soups! I put a few impressions on my Facebook timeline, even though Facebook is blocked by China’s Great Firewall. Its peepholes, so-called VPNs (virtual private networks), are officially forbidden even for foreigners, but woe if you don’t install these little assistants on your gadgets before crossing the border—your trip will be demanding without a solid knowledge of Chinese. For Google and its Maps are also blocked, along with the Facebook-Twitter-Wiki world and other sources of the bacteria of freely formed opinion. The Chinese are tied to the Alibaba-Baidu universe. Sure, the smarter ones all have VPNs. But communication mainly takes place via WeChat, the (enlarged) Chinese version of WhatsApp. WeChat is only used in the West by people who want to stay in touch with mainland Chinese. The censor’s arm is long.

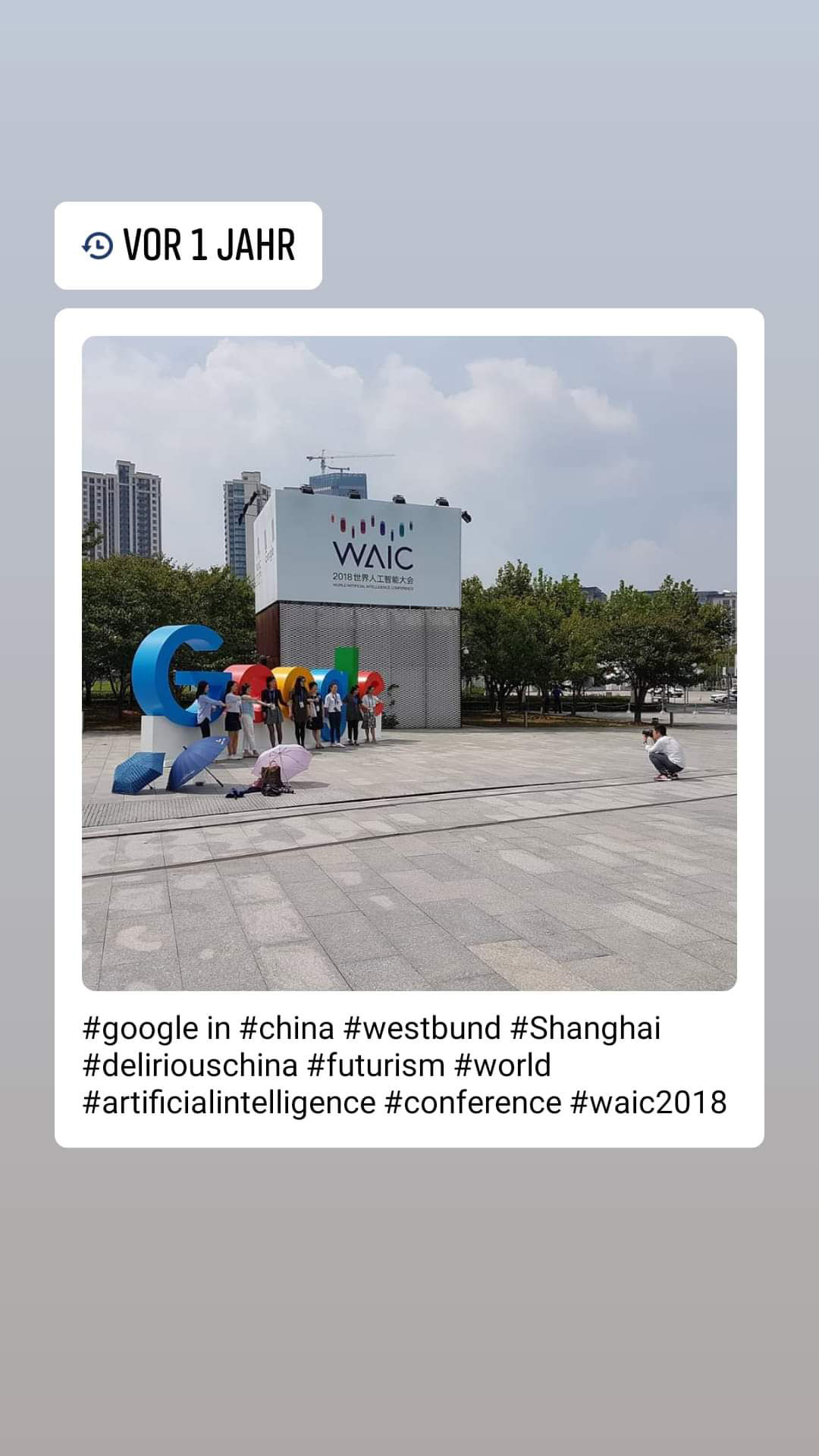

Google is a hot potato since it was banned in China in 2014. So I was amazed to encounter its logo in Shanghai, with crowds of Chinese youth taking selfies in front of it. It was standing in front of a new, mostly privately funded museum of contemporary art, the Long Museum Westbund. Westbund is a somewhat sterile showpiece district with hermetically sealed luxury high-rise buildings, new empty boulevards, a river promenade for jogging, and a big Audi dealer. It smells of boomtown.

The line of Chinese selfie-youth was standing in front of the Long Museum because the World Artificial Intelligence Conference WAIC was taking place there. Unfortunately the museum had been cleared out for it. My long journey was all for nothing. Though not quite, for I learnt a thing or two: in China an art museum can be cleared out for an event in no time; in China young people think Google’s cool, banned or not. What’s more, in China a World Artificial Intelligence Conference apparently doesn’t need Westerners. I puzzled over what “world” stood for. Perhaps for “world domination” through AI surveillance? My Chinese friends, enlightened as they pretend to be, don’t like to hear such things. How arrogant of Westerners to think of the Chinese as digital prisoners! A gross insult! Colonial trauma sits deep—and is propped up, so it seemed to me. In the end I learnt the official linguistic convention. “Surveillance”? No, this is just “progressive Chinese technology.” It’s superficially similar to the algorithms of Google and Facebook, themselves by no means harmless. But in the end what counts is who has a hold on the instruments, and with what authority—and whether there are ways to resist them effectively.

PS: There is a continually updated list of websites blocked in China at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Websites_blocked_in_mainland_China

Despite vehement criticism of his data kraken, Mark Zuckerberg thinks that FB is the lesser of the two evils compared with what’s on offer in China: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-10-17/zuckerberg-warns-china-s-censored-internet-could-still-win-out. The FB share is plodding along with a downward tendency.

Charlemagne Rides through Paris

Barbara Basting, 04.12.2019

Facebook’s algorithm has served up memories of my Turkish travels often enough, but now it’s taking countermeasures and suddenly presenting quite different entries from my so-called timeline.

For example, this blurred photograph of an equestrian statue of Charlemagne, unfortunately barely visible, with vassals. I had noticed him a few years ago at a late hour, when crossing the Île de la Cité in Paris, while he was riding westward from Notre-Dame. His creator, Louis Rochat, followed the recipe book of historical stage design from which historical heroes were cobbled together in the 19th century—and cathedrals too, as all the world knows since the blaze of Notre-Dame. You take, for example, a scepter, as stocked in the Louvre for just such reenactments. No matter that it belonged to Charles V, who was born 700 years later. You add in extras called Oliver and Roland. Who still knows that Roland was long dead by Charlemagne’s coronation? You ask Viollet-le-Duc, who’s puttering around Notre-Dame anyway, for a pedestal. Et vive Charlemagne!

Even contemporaries had their difficulties with the colossus. Conceived while Napoléon III still ruled, modeled in plaster for the World’s Fair of 1867, controversial after 1870 because of the war with Germany, cast in bronze in 1878, it was only purchased by the city of Paris in 1895 and placed in 1908: the year that Picasso and Braque rang in modernity with Cubism and heralded the deconstruction of the operatic realism so loved by the nineteenth century.

The church square was deserted when I photographed Charlemagne. No one on patrol, as it was before the major terrorist attacks. While busy with my smartphone, I heard something rustling, and in the flower beds I saw big fat rats eating leftovers from discarded packaging. I stamped my foot hard. They went on eating, unmoved.

I took a photograph of them as well, not without thinking with a shudder about Camus’s Plague. The eye of one particularly large creature glowed red in the flash. Later I posted the pictures of the monument and the rat side by side on Facebook, after Jean-Luc Godard’s adage that 1 + 1 picture equals a third. My diffusely imagined third picture had something to do with the eerie heroic pose of civilization and the no less eerie power of unmoved rodents.

But then Facebook suppressed the rat. Only the hero remained. Okay, Facebook doesn’t like the third picture. Either this is censorship, or the algorithm is overwhelmed by pairs of photos and the imagination located in their intervening spaces. This is cause for hope.

PS: For information on the monument I thank: https://lindependantdu4e.typepad.fr/arrondissement_de_paris/2009/06/la-statue-de-charlemagne-et-ses-leudes-une-statue-qui-a-eu-du-mal-%C3%A0-trouver-une-place-.html — Oh yes, Facebook’s share price has very much recovered despite the scandals around “fake news.” Here is the result of an inquiry by the British House of Commons: “Disinformation and ‘fake news’: Final Report”: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/ cmcumeds/1791/1791.pdf

Behind the Great Firewall

Barbara Basting, 26.10.2018

I sit in the lobby of a hotel in China where I am accommodated along with other guests of an academic colloquium. Set in the middle of a vaguely Tuscan landscape, it includes a golf course, a thermal spa, and an extensive colony of holiday homes. Skyscrapers and the Yellow Sea on the horizon. The region is considered to be the Chinese Riviera, and borders on the city of Qingdao. Under Emperor Wilhelm II it was briefly a German colony. Today the city is booming, and not just because of the German-founded brewery.

The lobby contains a children’s slot machine. You can fish for Walt Disney plush toys. Images of exploited workers in Chinese factories come quicker to mind here than elsewhere. When I access my Facebook page, I think I’m hallucinating, for the Facebook algorithm presents me with a souvenir picture of stuffed animals. Does their app now contain proximity readers?

I took the photograph on September 10, 2013, on Taksim Square in Istanbul. I was there for the Biennial. The Gezi Park protests had been violently put down in May. The atmosphere was palpably tense. The simit sellers were standing on the square with their old-fashioned trolleys as usual, as if nothing had happened, and as in previous years I bought one of the dirt-cheap sesame rings from a seller who told me he was a refugee engineer from Syria. Suddenly there was an alarming police presence by the numerous crowd barriers. The hitherto numerous passers-by dispersed with lightening speed.

One of the hawkers was making plush toys dance. I remember taking a photograph of them, because they seemed to me to be symbolic: distraction and placation in an uncomfortable situation.

I walked swiftly back to the Istiklal pedestrian zone. Groups of demonstrators approached me. Heavily armored vehicles with water cannons waited in the side streets. Busses released nervous young policemen in combat gear, wet behind the ears, prayer beads in one hand, gun in the other. Teargas stung my eyes at the English-language bookstore in Galatasaray, where I stopped briefly. I almost ran to where I was staying nearby. Heavy iron grating rattled down in front of the shops as I passed. Later I heard gunshots, shouts, and clattering. Next day I read that there had been no fatalities.

The picture of the Taksim animals awakens these memories, and superimposes them onto the sight of the animals in the Chinese slot machine while I am simultaneously trying to sort through my impressions of just a few days in China. Aren’t there certain similarities with Turkey, which I first got to know after 2000? A futuristic country, entirely devoted to progress. A proud society, whose winners demonstratively enjoy their privileges, as if in this way they could serve as models for all those who haven’t yet made it. Artistic and intellectual elites cautiously trying to create room to manoeuver. In Turkey it was a time when much seemed possible. Over and gone. No one can tell how a prospering consumer society will effect the centrally controlled Chinese state. Some wags say it all depends on whether the slot machine has enough plushies for everyone.

PS: the FB share is no longer doing very well, since the crash in summer. New problems are continually turning up, most recently a hacker attack on 50 million profiles: https://www.wired.com/story/facebook-security-breach-50-million-accounts/

Sign of an FB twilight? The Chinese have other worries. For them Facebook & co.

lie beyond the Great Firewall.

Boutiques on the Bosporus

Barbara Basting, 10.04.2018

I’m no longer very happy with Facebook. Recently the algorithm seems to be taking the platform into total despotism. And on top of that it’s continually being altered. Just when I’ve gotten used to the comforting stream of souvenir images, Mr. Zuckerberg decides to do away with them. Or is it my fault again, for not liking and sharing enough?

How wonderfully simple the old algorithm was. During a time I was often in Istanbul, it actually noticed that I was often in Istanbul. Perhaps five times in a row my snapshots from there were served up for compulsory recollection.

What you see here are the shoddiest of them all. While wandering around I came upon these sequined caryatids and the rather oppressive stairwell they lined.

We’re near the subway station Osmanbey, on the European side of Istanbul. Here there’s a cluster of boutiques offering religiously compliant ladies’ fashion. High-necked, long coat dresses, for example. No, not those dismal beige sacks, but fitted creations in colorful fabrics. Hoods instead of headscarves. Some of the patterns are really stylish and made for slim, gazelle-like women. And here and there you often see store windows with fantastical eveningwear that puts what you see at the Oscars in the shade.

I’d like to inspect the boutiques more closely. But I withdraw cautiously after noticing that the staff always consists of three men, usually two younger ones and a boss. They eye me disapprovingly through their windows, before which, clothed in jeans and sneakers, I stand and stare in like a child in an aquarium. Seeing straight away that I don’t belong to their customer segment, they turn to their tea glasses or the recently delivered, Chinese-labeled bales of dresses tightly wound in kilometers of plastic wrap.

Somewhere I read stories about Istanbul’s booming fashion scene. They gave the impression that Istanbul was inserting itself into a list of the Paris-London-New York-Milano-Tokyo sort. I mulled this over. Perhaps I had to reconsider my understanding of fashion.

Later, in the endless screening line at Atatürk Airport, my eye was caught by a group of black-veiled women heaving enormous trunks and packages covered in brown duct tape onto the conveyor belt. I guessed what was in the packages. Istanbul, that much I knew, is now the shopping mall of the Middle East, and what was once the Silk Road junction is now a polyester hub. I still regret not having climbed the stairs in Osmanbey, by the way.

PS: Following news of the abuse of Facebook’s user data by Cambridge Analytica for Trump’s election campaign, the Facebook share has sunk to 165 dollars.

This shouldn’t surprise anyone who knows John Lanchester’s profound analysis of the kraken that the platform is: https://www.lrb.co.uk/v39/n16/john-lanchester/you-are-the-product

The issue of “bots,” i.e. fictive followers, is nowhere near over:

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/01/27/technology/social-media-bots.html

12 Feb 2011 — 12 Feb 2017

Barbara Basting, 24.03.2017

Facebook recently wanted to make merry with me. To this aim it posted an entry on my notice board, which is actually closed to others. Because of the trolls. But for the FB people this barricade apparently doesn’t apply. Must be in the small print. The post I’m now sharing was somewhat unsettling: “Barbara joined Facebook 6 years ago!” I recognize my profile picture on the largest button. A selfie I took some time ago in front of a very corrugated silver-foil wall in an exhibition by Joëlle Turlinckx in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Basel, and in which I look like a streak of oil paint. Absurd attempt at camouflage. On the smaller buttons I recognize the selfies of my so-called Facebook friends. In the middle of the button salad an arrow. An animation to click on.

Here an urgent warning. It’s cringeworthy. A mockery. As thanks for all the years of FB membership I’m offered a mediocre animation in the style of a somewhat inane children’s book. It shows a balloon rising into the air with a wow-smiley and a card with my first name hanging from it. Then comes the text “Today may be just another day. And yet it’s something very special.” Why? Because it’s my Facebook anniversary, of course. Apparently I’ve been on Facebook since February 12, 2011. The animation then presents me with a pinball machine with the magic date on a calendar page on top. Then like-love-rage buttons race through the gadgetry like pinballs, and along with a few pics from my past—called my “timeline”—the machine emits a spinsterly sigh of “How time flies!” The following five or six photographs have been fished out by the algorithmic ladle.

This so vivid presentation of my Facebook anniversary warrants a comparison with my hitherto service anniversaries as an employee. It’s the way of the world that sitting tight in a job is no longer acknowledged as generously as it used to be. On the whole you can be glad if you’re allowed to stay, or if you can stand the work long enough—and in particular if it isn’t just supposed to provide you with a living but also, quaintly, with meaning and work fulfillment. The unpaid work for Facebook is unconvincing in this respect, I’m afraid.

It does, at least, provide some gratification in the form of likes and free souvenirs. To be more exact these are algorithmically generated chance and forced souvenirs. I recently read, in a clever and most enlightening study by the literary theorist and social-media expert Roberto Simanowski, that precisely because of their algorithmic randomness these souvenirs, these memories are never joined into a genuine, coherent narrative, but only bait us with the illusion of one. Sadly, I admit it, this visual bait works fine with me. Because Facebook does without material gratification and remuneration, I have decided to participate monetarily from now on in the success, to which I have contributed, of the network as an advertising platform. For my Facebook service anniversary I have purchased a Facebook share (entry-level price: around 133 dollars). Now we’ll see how the trade in illusions develops.

12 May 2011 – 12 May 2017: On Non-Digital Storage Media

Barbara Basting, 24.03.2017

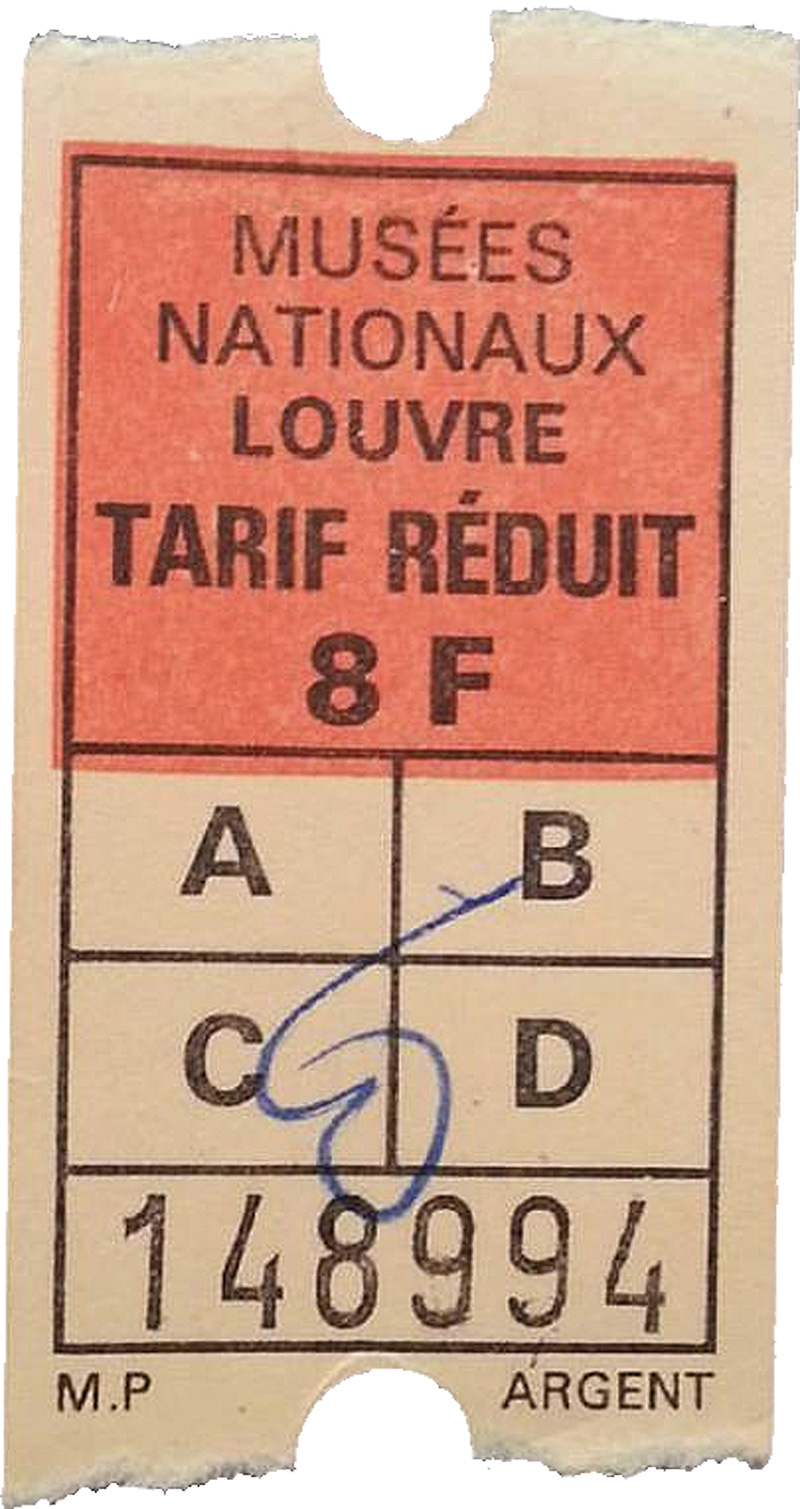

The Facebook algorithm has noticed that I have something to do with art and museums, and presents me with a snapshot of a Louvre ticket from the pool of my earlier posts. At the time of the post the scrap of paper had already survived for years as a bookmark in a non-digital storage medium, a paperback from my time as a student in Paris.

Back then my day at the Louvre was always the first Sunday of the month. Free entry! Too bad that the side cabinets with Dürer and Vermeer were only open on weekdays, when students were entitled to the “tarif réduit C.” Half price, eight francs: equivalent to three baguettes. Today the Louvre is free for the youth of the EU under 26. The full price is 15 euros, equivalent to at least fifteen baguettes.

Mind you, the Louvre is now a great deal larger than it used to be. The “Grand Louvre,” with I.M. Pei’s hotly discussed glass pyramid, was one of President François Mitterrand’s “grands projets.” He led a cultural offensive along with his minister Jack Lang, as if this might save the already dented “grande nation.” No government since then has believed so resolutely in the reforming power of culture. The only foolish thing was that even the socialist Mitterrand was royally fixated, as it were, on “grandeur”—and on Paris.

The Grand Louvre is a huge success with tourists, and the most frequently visited museum in the world. But despite its expansion to Lens, into an economically stricken province, and the opening of an Arts of Islam gallery, the cultural belief that a Louvre could strengthen social cohesion has evaporated. Such manoeuvers, like the controversial founding of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, served more to focus a cultural-historical brand.

But suddenly now this: the newly elected French president, Emmanuel Macron, uses the neo-pharaonic glass pyramid, of all things, as the backdrop to his first speech, and sets the bar high in referring to its “audacity” and the Louvre as a founding icon of republican culture.

Not only in the light of such emotionalism do my visits to the Louvre in 1984 feel like time-capsule dives into the nineteenth century. At their heart were the Grande Galerie, the Italian collection, and the halls with the sublime historical daubs of Delacroix and Géricault. You just stood there and tried to make something of them.

For the Louvre, that product of the French Revolution, from which its founder Vivant Denon wanted to make a people’s museum, was still a museum of the elites in 1984. Communication, apart from date and title: zéro. But it was a treasure trove of art before the flood of images, a museum before the museum shop, the museum selfie, and solicitous impartation. There was nothing except the art. So you tried to understand what this art was. If you didn’t understand it here, where else?

It was all cloaked in magic, which for me has been lost in the oiled wheels of the art-consumerism machinery with direct shopping-mall connection. The ticket from 1984 has unexpectedly become the entry into this yesterday world.

PS: The share is fluctuating around 150 dollars. Ex-Facebook executive Antonio Garcia-Martinez reflects in the Guardian on Facebook’s ethical problems with target-group advertising: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/may/ 02/facebook-executive-advertising-data-comment. And Internet critic Geert Lovink asks in his recent book: “What is the social in social media?” http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-1509507760.html