Sprache

Typ

- Buch (6)

- Wissenschaftlicher Artikel (2)

- Interview (0)

- Video (0)

- Audio (0)

- Veranstaltung (0)

- Autoreninfo (0)

Zugang

Format

Kategorien

Zeitlich

Geographisch

User account

About ‘how we treat the others’

Conversation on “Glimpse”

Artur Żmijewski in conversation with Michael Heitz

Published: 03.07.2017

Michael Heitz: Glimpse shows us scenes filmed in various places. How long did you stay at these places? Was it already known that Calais would be cleared when you started the project?

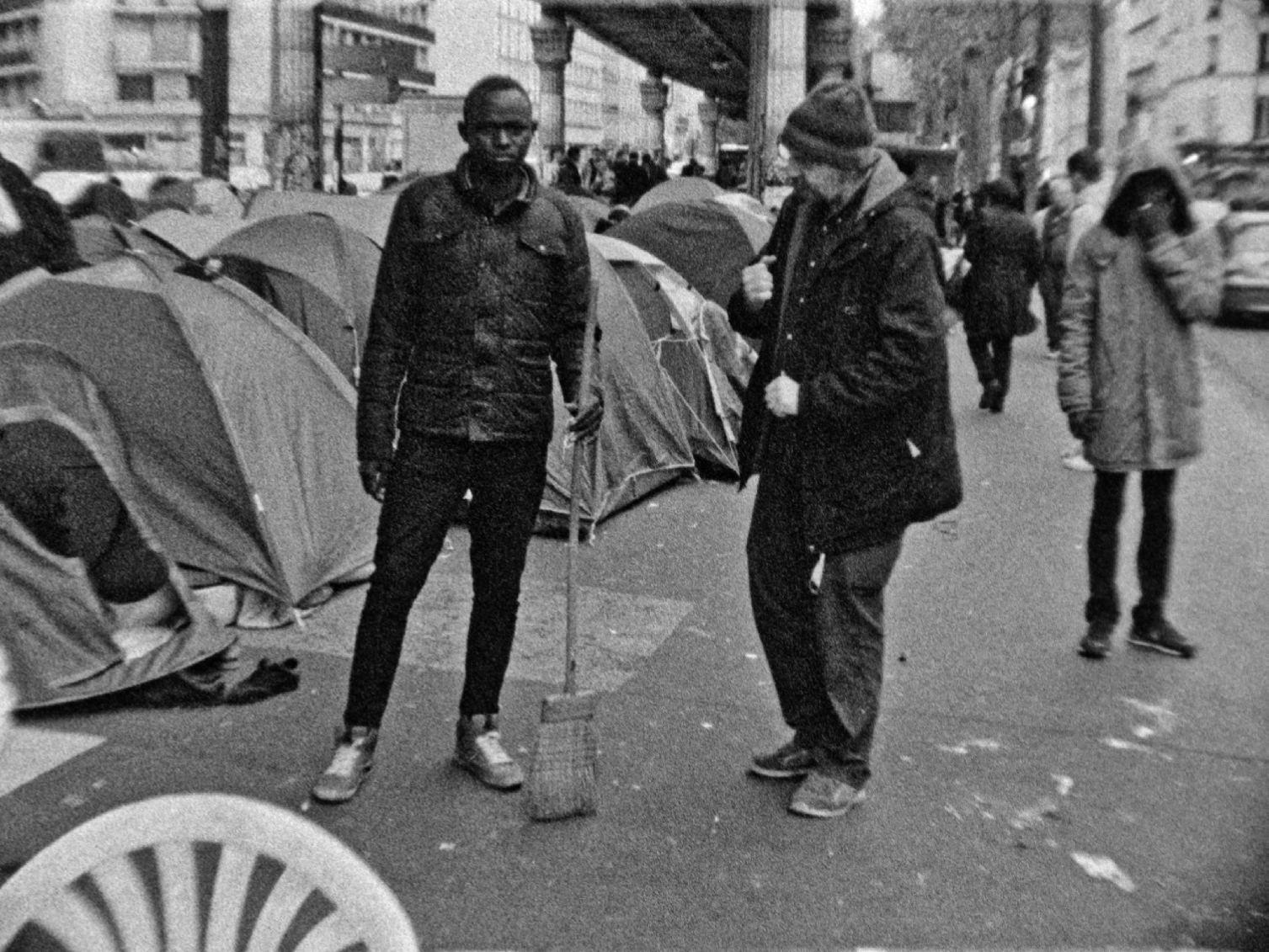

Artur Żmijewski: We spent more than one month filming in Berlin, Calais, Grande-Synthe (the suburb of Dunkirk), and Paris. Yes, it was announced that the French administration was going to “clear” the Jungle in Calais. It was also quite obvious that refugees would be removed from the streets of Paris. Such places, like the surroundings of Jaurès or Stalingrad subway stations, were full of immigrants living on the streets. Police forced them to leave. Some of them were relocated to the camp close to the Porte de la Chapelle. Hundreds of people were living on the streets close to this new camp. So we were filming in Calais, then in Paris in different locations—following policy of the French administration.

Can you tell me some details about the situation and the conditions that you found in the camps and something about your concrete state of mind that compelled you to do the work?

The conditions in the camps were extremely basic—people were living in tents or wooden kiosks in winter. In many cases whole families were waiting months for nothing. Many people in Calais or in Grande-Synthe were desperately trying to enter UK territory, but the French police were blocking them. People lost their property and had to rely on the support of the others: usually NGOs or activists. There is something deeply humiliating in such a situation.

There was and still is a specific way of talking about refugees in Poland—even if there are not really refugees in Poland: “They are potential terrorists”; “They spread exotic bacteria and viruses”; “Instead of escaping to Europe, young guys should keep guns and fight for their countries.” These were and still are opinions presented by the main political figures in government and state administration. It’s a way of talking which is also popular in other Eastern European countries. I wanted to try that kind of talk.

You once described “Art as an intuitional tool.” What is the intuition here?

Intuition helps artists to follow something behind the rational level, the level of rational thinking. In this case I was trying to follow a specific way of filming proposed by propaganda filmmakers and also to activate my own fantasy—and to propose specific behavior towards refugees.

How did you prepare the persons involved?

I was working with a small team: a cameraman and two assistants. This specific work was based on improvisation. With people living on the streets you can’t prepare anything in advance. We were present on the spot—in Calais or in Paris, where the refugees had built their tents—and we talked to the people, looking for those who could agree to be filmed. We offered jackets, shoes—or in some cases money as a fee for this “job.” They weren’t really actors. They are people living in tragic conditions who decided to “cooperate” with my team. We informed them what we were doing and why—also about the expected presentations in an art context.

How would you describe your role as an actor in the film?

I represent an “abstract” white European guy who transforms his doubts into specific behavior towards the refugees, strangers. But I don’t perform myself in the movie—I perform a specific persona, “someone” or “each” who doesn’t feel blocked by political correctness to make bad things on a public forum. This abstract persona follows the general permission to treat strangers badly.

Since any person in a film is always representing something or someone else, I doubt it’s that simple, or even possible. Do you really intend to neutralize your own role as artist, director, actor, author?

This persona is the equivalent of the “subject” in literature or the actor in a movie. It’s not “I” or “Me”—it’s rather “Each” or “Every.”

Thinking about the important role of experimental procedures in your former works and your writings, I wonder if you worked with any hypothesis in this case?

Yes, the equivalent of the hypothesis can be the task to translate verbal speech into a stream of images. Very specific speech—cruel, focused on exclusion and symbolic (but finally real) atrocities. That’s the speech formulated by right-wing politicians. But in this case even the democratic center represents the agreement (which goes across political life, political institutions) about keeping hard distance from refugees and their potential needs.

How do you deal with post-production?

Post-production, specifically editing, is the moment when you can discover “the story” that was filmed and try to present it in a very clear and direct way. Editing is also a slow process in which intuitive choices are mixed with rational decisions. The goal is to create a story—direct message, something touching.

Can you describe what has been produced?

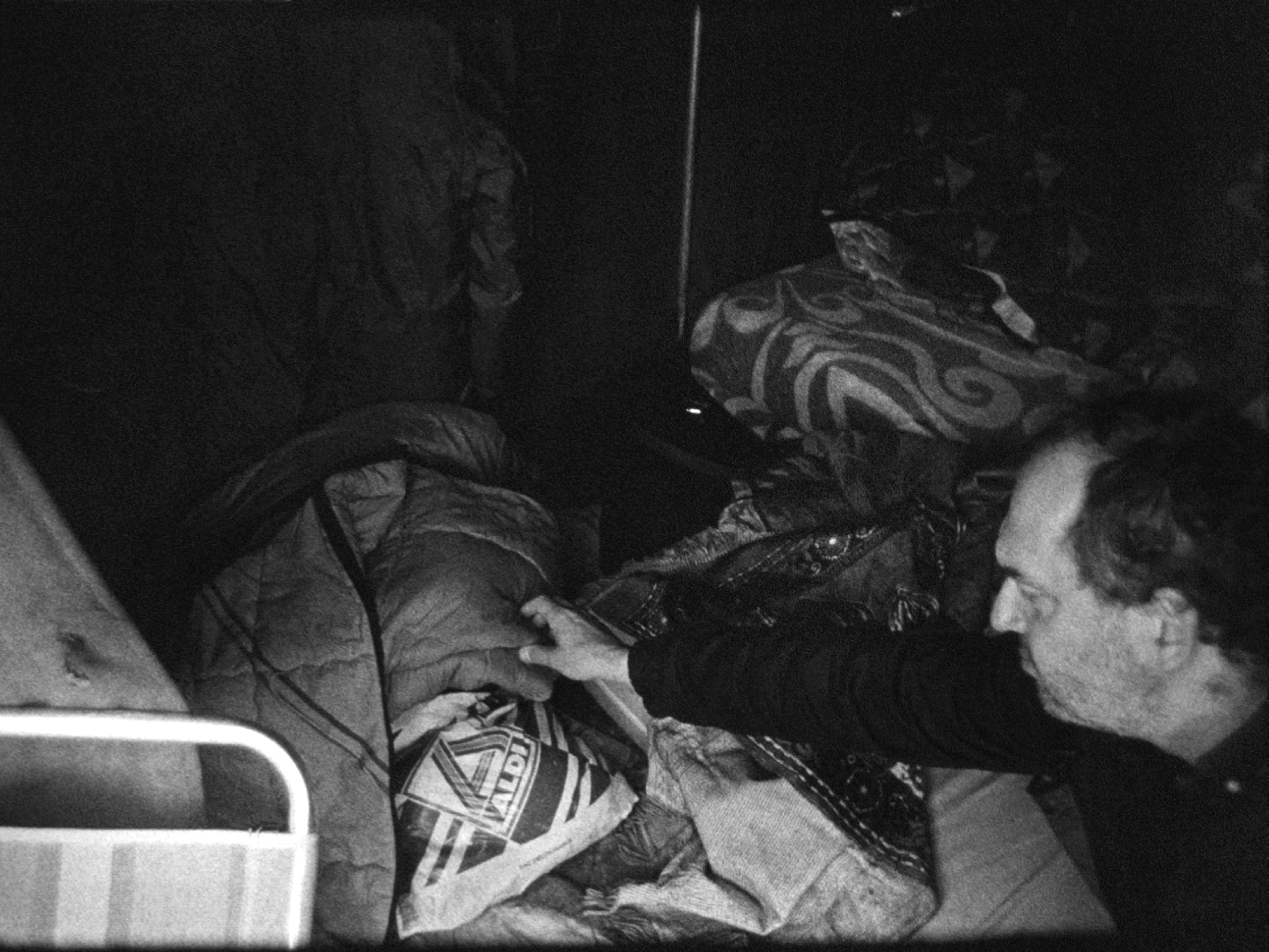

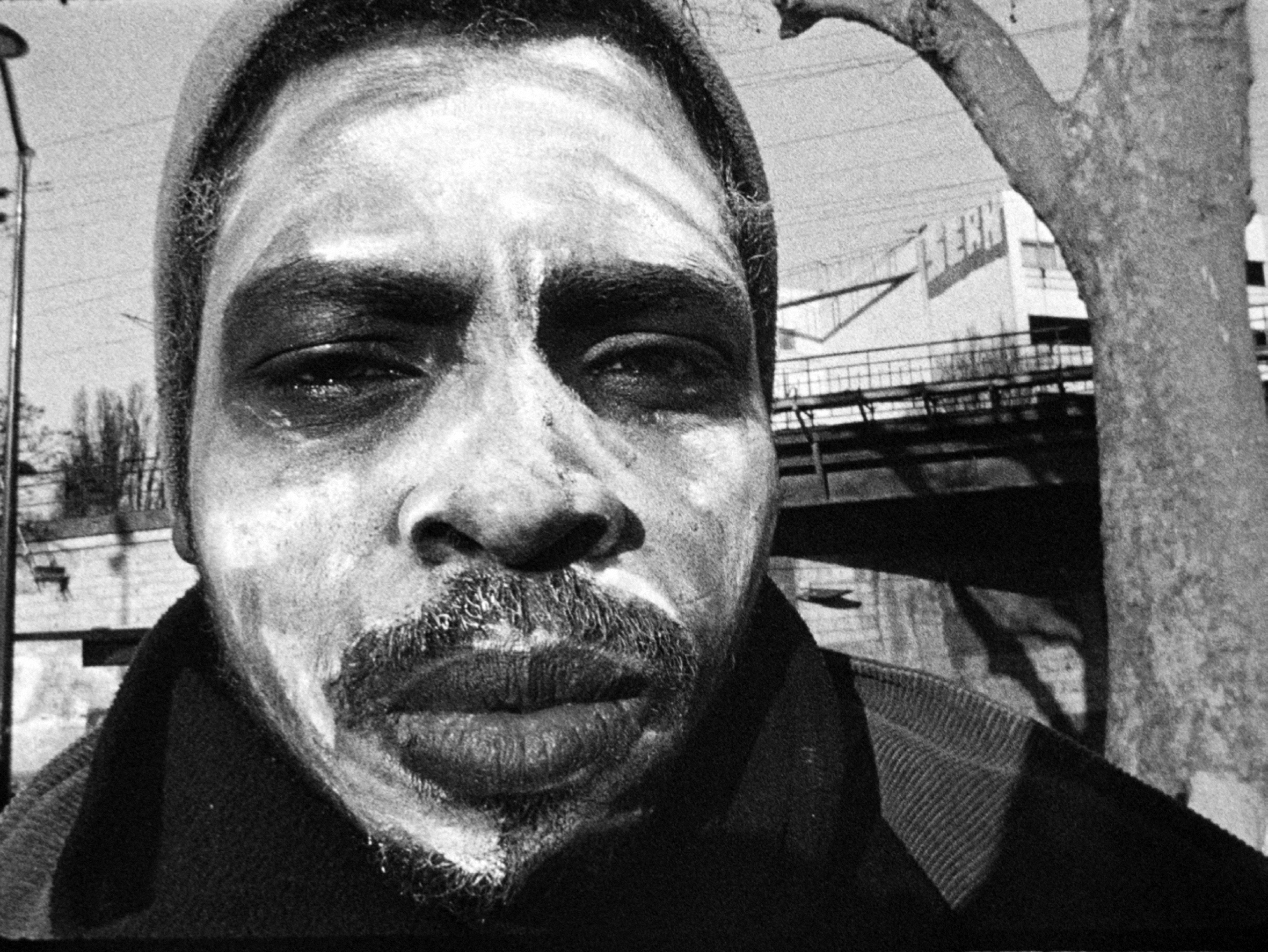

The final result is a movie based on a half-documentary, half-creative approach. The movie presents conditions in which immigrants live: tents and primitive barracks, interiors full of blankets, coverlets, and collected food (milk, sugar, flour, and so on), dirty surroundings—the whole human life radically reduced to its vulgar and primitive forms; the movie also presents a few performative actions: the “donation” of shoes and jackets, painting a white cross on someone’s back, manipulating immigrants’ heads, painting the face of a black person white.

The movie proposes a certain form of presenting immigrants—black-and-white images, central composition, a didactic way of showing people, long judgmental panoramas, semi-amateur shots, and non-professional use of the camera, low-quality negatives with high contrast and shaking images. This is a kind of conscious replica of the propaganda forms that were present in the movies made by soldiers or political functionaries in 1930s, 40, and 50s in Europe.

Regarding this doubling of bad treatment, do you believe in any pedagogical or even cathartic moment of your art, of art in general?

I do not teach viewers, and I do not propose therapy—I perform an ambiguous act that isn’t based on rational expectations. It’s rather a way I can dig deeper into collective violent and distanced behavior towards immigrants, towards the others.

In your manifesto “Stosowane sztuki społeczne” (“Applied Social Art”) you designate the sense of shame as one of the emotional fundaments of art. Do you feel the shame imposed by the film?

I mentioned shame in the context of propaganda, agitprop, and the non-democratic use of art as a tool in the hands of mainstream political forces. It happened in Poland, in the Soviet Union—in the whole former communist block. This involvement caused traces or remains: a shame.

But I do not feel shame when I make my own movies. And it’s not shame to hate the others nowadays—that’s the new message of the primitive propaganda of the Law and Justice party in Poland.

But some of the refugees obviously did feel ashamed. I’m not interested morally judging of your work, rather in the relation between ethics and aesthetics. Can you tell me some of your thoughts on this?

The relation between ethics and esthetic is exactly about moral judgement. They felt ashamed because it’s shameful to have nothing and rely on other people with no opportunity to offer them something back. I think that they feel their negative value. They are present but they shouldn’t be there; they should disappear, sink in the sea or be frozen in their tents. They are like living deaths from the Agamben book—social “Muselmänner” facing their own lack of value in Europe …

… while looking at the viewer of the film. Thinking about the title, Glimpse, it seems to me that it’s not only about admitting the necessarily restricted insight in the situation of refugees, but also about emphasizing the role that the gaze is playing into the film. The gaze of the refugees and the gaze of the viewer. Sometimes they meet. These are shameful situations, but also moments where recognition, even appreciation is made possible? Can you accept such interpretation?

No. The movie doesn’t present any real situations (even if this isn’t true)—actions are staged, performed. I would suggest understanding Glimpse not as a meeting of real people who commit certain gestures and look at each other, but as a metaphor—a strongly condensed message about “how we treat the others.” This metaphor is painful, but the role of metaphor is to take a short cut. Like in a poetry—very few well-aimed words in effective configuration instead of long rational explanations.

In any case, most of the time the camera acts like a voyeuristic weapon, as a tool for humiliation. Can you tell me a bit more about this?

The camera in Glimpse is a judge. It watches people from a defined perspective—it isn’t obvious that the people who are presented are fully human. Maybe it’s another race … For sure they look ugly and live in ugly conditions. But that’s how propaganda works—such a discourse has a goal which is usually un-justice. I live in a country where it’s socially accepted to declare: “I do not want any strangers in the country.” It’s understood as example of political bravery when someone breaks political correctness. And such a declaration was generated by the leaders of dominant political forces in Poland. So I wanted my film Glimpse to keep this perverted position and declare “the same.”

But why did you decide to use Nazi and other sorts of totalitarian film rhetorics at all?

Because to build walls on borders, to demand the return of boats with immigrants is a semi-Nazi rhetoric. People die at sea trying to reach European land—to force them to go back is kind of genocidal. I wanted to translate verbal hate speech into a visual one. This hate speech is everywhere around us—performed very often by high-ranking officials of the dominant political forces in Europe. What I do is translation. Instead of hearing the sound of this speech, you can watch it. The meaning is the same—it’s consecutive translation.

Your film is no work of propaganda though. What is the specific difference?

It’s in a gap between propaganda and a certain strategy of how to perform a kind of self-reflected hate speech that at the same moment can be discredited for being a hate-speech-like attempt. So it’s designed as an ambiguous message that contains elements of working propaganda. But it also has a self-destructive system that can be activated by the viewers (like the self-destructive system in the spaceship Nostromo in the first movie from the Alien saga—activated by Ellen Ripley when the horrible creature appeared on board).

This reminds me of a comment by the Slovenian music band Laibach: “All art is subject to political manipulation, except for that which speaks the language of this same manipulation.” Assuming this, no more critical or ironic distance is possible; other forms have to be applied instead. In your example of inserting a self-destructive system, I wonder what exactly is object of such destruction?

Contrary to the opinion you quote, an artist is able to occupy an autonomous position and take decisions freely (it’s probably impossible in murderous political regimes).

What is questioned, what becomes an “object,” is ambiguity itself. Because the movie presents ambiguity towards immigrants in a radically pure form.

Do you visit public screenings, and are you interested in observing the effect on the

viewers?

No, I don’t deliberately observe the viewers of my films. I don’t control what viewers think about my movies. I make a proposal—in the form of a film. But I’m also ready to explain my opinions via texts. I’m ready for debate.

What could be possible courses?

It’s not a science—it’s an emotional message generated by rationally found visual strategies. We have imprinted in minds, in collective memory, these brutal propaganda images from old movies, this specific judgement coded in images of the others. Maybe the viewers feel a wave of emotions in confrontation with such a visual hate speech. The message is: it looks like it happened in the past (because of the old-fashioned film technique), but it happened this year, now. So maybe during these decades there wasn’t a tectonic shift in the way we are able to treat “the others.”

But the effects on the viewer are a crucial part of your work, aren’t they?

Yes, but I don’t control spectators—do you think it’s possible to predict how people will react? Propaganda movies from the past supported conflicts or played a role of state-given permission to celebrate or perform hate. My movie doesn’t play such a role—its main character declares this openly—because these day we are allowed to perform hate speech without any shame: “I’m a white European guy who watches poor immigrants and thinks badly about them.” We aren’t in clinic that could propose a better understanding of our nationalistic approach to us—we’re in this hellish place where a human being starts to be nothing, has no value—has anti-value. Disrespect instead of respect—tough distance instead of space sharing.

You once said: “My films are arguments and are under examination.” Since the Athens show has been open to the public for several weeks now and had its first reviews, have you already received anything that you would call an examination of Glimpse?

It’s too early, I think.

Glimpse (2016–2017)

Digital video transferred from 16 mm film, black-and-white, no sound

Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zürich and the artist

Artur Zmijewski, whose current film, Glimpse, was described by the New York Times as the most important exponent at the documenta in Athens, seems to be so clearly identified with his role as a provocateur that impassioned discussion about his work, which surveys the boundaries of political art, have become rare.

Contrary to the film Realism—which is being shown at the documenta in Kassel—in which men amputated at the lower leg confidently act, pose, and play a sophisticated game (apparently) in conjunction with the artist, the work for Athens proceeds from an acute initial situation. In his 16mm silent film of people blighted by flight and hardship in refugee camps, Zmijewski shows staged scenes like those familiar from National Socialist and Stalinist propaganda films.

Zmijewski’s frontal, quasi documentary visual and storyline rhetoric not only deliberately makes the refugees once again the object of an examining gaze and demeaning gestures but also forces them into a precarious face-to-face with the art audience. Whether this audience sees itself reflected in the trans-historical patterns of a xenophobic public or participates in the implosion of its own self-assured sympathy is left to personal interpretation and public debate. What is certain is that Zmijewski sets the stakes high and pushes discomfiture into the unbearable. Despite all negation, aren’t there still vestiges of a humanist aesthetic in the film’s stringent artistic experiments and their mimetic violence?

- documenta

- propaganda

- Poland

- concentration camp

- National Socialism

- political aesthetics

- gift

- ethics

- contemporary art

- migration

Artur Zmijewski

is a visual artist, photographer and filmmaker. From 1990–1995 he attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw at the sculpture department guided by the Polish avant-garde artist Prof. Grzegorz Kowalski. Żmijewski is one of the most prominent radical figures on the Polish art scene.

-

Philosophy in Action. Gerald Matt in Conversation with Artur Zmijewski ABO

In: Tobias Huber (ed.), Marcus Steinweg (ed.), INAESTHETIK – NR. 1

-

- Copyright © 2026 DIAPHANES

- About

- Press

- Trade Info

- Contact us

- Privacy Notice

- Masthead