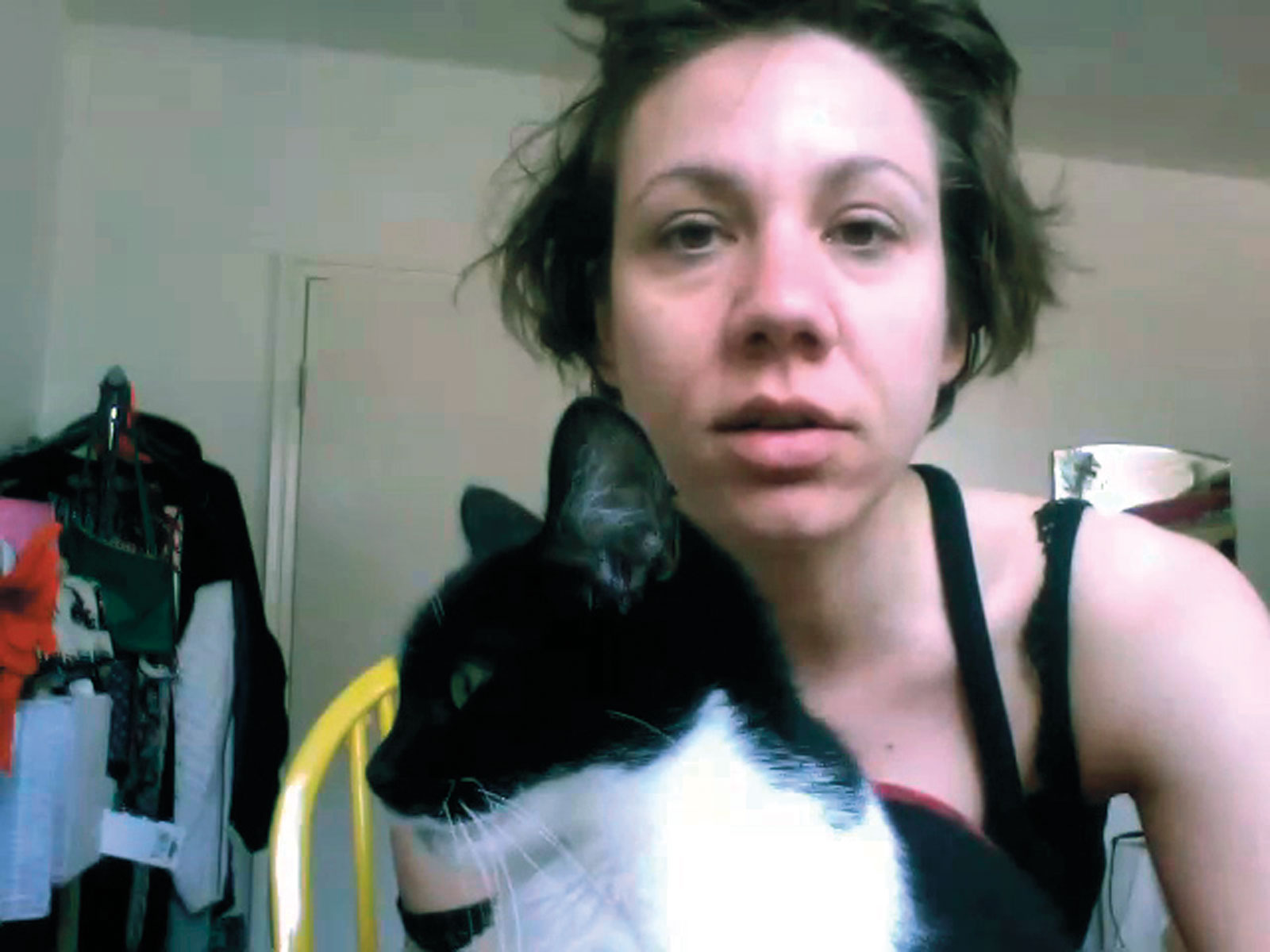

“Fear of public speaking, stress, anxiety, yoga breathing exercises, let-her-go lyrics, brain exercises, increase brain memory […]” chants a young woman into the webcam, her face frozen in an emotionless mien. Video sequences in rapid succession, bundled together under the names of months, show the artist Erica Scourti in a seemingly informal setting and at times quite unkempt, with puffy face, rings under her eyes and tousled hair, uttering strange phrases, all jumbled together, mainly about objects, feelings and places relating to the fields of music, art and religion, well-being and health, sexuality and partnership. Remarkably often, these fragmented utterings, spoken with relentless equanimity, are shorthand for physical or mental dysfunction and personal inadequacy as well as techniques for self-improvement or coping with anxiety and stress.

For this work, Life in AdWords (fig. 1–3), Erica Scourti wrote regular diary entries between March 2012 and January 2013, which she sent to her Gmail account.

Fig. 1–3

Erica Scourti, Life in AdWords, march 2012–january 2013

(11 parts), video stills, webcam videos, total length 1:09 min.

In a second step, she accessed the scripts automatically generated from her diary entries by Google using algorithms which translate the personal information in emails into consumer profiles that can be individually targeted by online advertisers. The artist then took these combinations of keywords listed in the Google scripts – a viable economic commodity, sold at highly lucrative rates to advertisers – and recited them, in slightly edited form, on a daily basis in front of her computer webcam. Despite – or perhaps even because of – its simple and almost casual format, the resulting work goes beyond merely conveying the descriptive personal mantra of a stressed artist, and actually delivers salient commentaries on the status of the subject in contemporary societies under advanced capitalism. In this respect, Life in AdWords offers an excellent starting point for the following deliberations, which explore the current situation of the subject, identity and self-perception in Western society by taking a look at how the self is portrayed and reflected in contemporary and emerging art.

Digital Self-Representations

People use representations of themselves – be they visual, written, material or mental – as an aid to securing the self, even though the precarious balance that exists between the representation and the represented is already well known. According to Zirfas and Jörissen, in spite of any misgivings about the self-image, it is nevertheless something that allows the subject to distil his or her own relation to the world into something “comprehensible and tangible,” and “stabilising unstable constructs of identity.” The authors also note the “reflexivity of the subject in relation to the image of the subject” in the sense that the representation of the self has a retroactive effect on the subject. Even though, as Florian Cramer quite rightly emphasizes elsewhere in this publication, “All overly simplified, media-ontological explanatory models claiming new media as the autonomous source of dispersed authorship and” of identity, in whatever form, should be ruled out, it nevertheless cannot be denied, given the close reciprocal interweaving of representation and identity, that new digital communication technologies have expanded and altered the possibilities of self-portrayal and self-perception in ways that are of indubitable significance in terms of subject formation and questions of identity today. Erica Scourti, too, when speaking of her work Life in AdWords, points out the close reciprocal interaction between self and technology, with reference to a quote from Donna Haraway, saying that “it is not clear who makes and who is made in the relation between human and machine.” At the same time, the artist also highlights the unbridgeable gap between the representation and the represented through the amusing dissonance between the apparently natural and realistic webcam images of her supposedly authentic self and the synthetic, machinic language. By pointedly addressing this discrepancy, Scourti deliberately emphasizes a blind spot that occasionally occurs in self-representation on (net-based) digital media. In this respect, the “dynamic and continuous” interaction between humans and digital media “with feedback and feedforward loops connecting different levels with each other and cross-connecting machine processes with human responses,” as Katherine Hayles describes the interaction between human and machine cognition in general, could indeed suggest a direct link-up between the self and its media representation. While this sense of being linked up to one’s virtual self – which Scourti explores through the feedback loop of the Google script pertaining to her – may not necessarily lead to a “fractal self” or split identity, it might nevertheless lead, at the very least, to a constant media-based re-appraisal of the self, given the seemingly minimized detachment from this technologically presented self-reference.

The Subject as Commodity

The digital representation of the self – as the work of Erica Scourti so clearly demonstrates – not only results in a technologically supported self-reference, but also, and more importantly, offers the perfect conduit by which the subject can be channelled into the global circulation of information, commodities and capital. The translation of Scourti’s personal diary into consumer-relevant data and the artist’s reiteration of this illustrate the transformation of the subject into stereotypical consumer profiles that are simultaneously created and digested by the capitalist machinery of neo-liberalism and which, in turn, rebound on the subject – often unwittingly – as a result of targeted use value promise. The digital representations of the self in and through email programs, search engines, blogs and social networking sites are not necessarily the initiators here, but they are certainly busy helpers in the creation of the very thing that untrammeled capitalism seeks. “What the neo-liberal market forces are after, and what they financially invest in,” according to feminist theoretician Rosi Braidotti,

is the informational power of living matter itself. The capitalization of living matter produces a new political economy, which Melinda Cooper (2008) calls ‘Life as surplus.’ [...] Data banks of bio-genetic, neural and mediatic information about individuals are the true capital today, as the success of Facebook demonstrates at a more banal level. ‘Data mining’ includes profiling practices that identify different types or characteristics and highlights them as special strategic targets for capital investments. This kind of predictive analytics of the human amounts to ‘Life-mining,’ with visibility, predictability and exportability as the key criteria.

The all-encompassing commodification of life, the transformation of the subject into a commodity to be traded for profit, can be seen as an essential component of a systematic drive to productivise every aspect of life, famously described by Michel Foucault as “biopolitics” of the population and later was adopted and expanded by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri in Empire to describe the current state of global capitalism. Empire outlines a world-spanning, self-preservational, self-justifying system in which not just labour but all possible cognitive, physical, identificatory and emotional processes, right through to social networking, are exploited as human resources.It casts an image of a collective biopolitical body, of a society, which is “subsumed within a power that reaches down to the ganglia of the social structure and its processes of development,” and “reacts like a single body.” This viewpoint can also be found echoed in other contemporary works of art – notably in Melanie Gilligan’s Self Capital (2009, fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Melanie Gilligan, Self Capital (Episodes 1–3), 2009, video still, HD-Video, 27 min.

This Canadian artist presents the protagonist of her work as the personification of the global economy – as a capitalist social body – and at the same time as an individual subject whose physical and emotional state is inextricably melded with the capitalist system. The subcutaneous networking of the individual with contemporary capitalism, right down to the veins, arteries and nerve tracts, results in a reactive unit subjugated in the most negative sense to a “reactive bond of vulnerability.” Several years earlier, the American author Don DeLillo had also woven the fate of the main character in his novel Cosmopolis (2003) closely together with the vacillations of the market and had, notably, equated the cognitive processes of the young asset manager with the information and data flow of the capitalist system, which he described as part of the “life process” and “the heave of the biosphere.” The ruthlessly efficient protagonist, Eric Packer, comes across as the very embodiment of neoliberal global capitalism and yet at the same time as a victim of the selfsame biopolitical system he represents. The concrete process of the subject becoming-commodity is expressed not only in Erica Scourti’s Life in AdWords but also in a contemporary – albeit aesthetically very different – way in Ryan Trecartin’s Autumn 2010 fashion shoot for W magazine (fig. 5-6).

Fig. 5

Ryan Trecartin, Negative Beach + Lizzie Fitch, 2010, C-Print, 91,4 × 61 cm (portfolio for W Magazine, November 2010).

Fig. 6

Ryan Trecartin, Again Pangea + Telfar Clemens, 2010, C-Print,

91,4 × 61 cm (portfolio for

W Magazine, November 2010).

Trecartin’s series shows subjects so interwoven with various labels and products that they appear to have succumbed entirely to commodification and become utterly ensnared in digital visual worlds or in some virtually contracted process of disintegration. The products, accessories and labels seem strangely out of place. Externally applied, like some crazy bricolage, and yet at the same time organically internalised, they convey momentary snapshots of people who, on the one hand, seem numbed and derangedly sinking in a hypnotising flood of images, trends and commodities, yet on the other hand look as though they are united and militantly armed with these same consumer goods and icons as a means of coping with the sheer madness of the capitalist future.

The real perfidy of the capitalist system classified as biopolitical, however, lies in the fact that it operates under the guise of freedom, emancipation and individuality, offering promises and norms that drive the subject to constant self-evaluation in pursuit of neoliberal perfection. This “work on the self” does not serve the individual as much as it serves the profit maximisation of a capitalist system designed to exploit the gains of self-optimisation directly. Hence, a truly free experiment in self-fashioning is rendered impossible. For although the subject, as Rosi Braidotti recently noted, may be given the impression of individualism through “a quantitative range of consumer choices,” in actual fact this merely “promotes uniformity and conformism to the dominant ideology” – the dominant ideology being Western capitalism with its normative rules and values tailored to its own self-preservation and expansion of power. For Maurizio Lazzarato, however, the promise that this “work on the self” triggers a process of emancipation encompassing joy, self-realisation, recognition, mobility and experimentation with various lifestyles, is directly linked to “the imperative to take on the risks and costs that neither business nor the state are willing to undertake.” In other words, the individual not only has to evolve in conformity with capitalism and, in doing so, achieve the greatest possible commodity-driven profit maximisation, but the individual also has to bear all the risks that this entails and must ultimately accept full responsibility for the success of this supposedly emancipatory endeavour.

We find this “work on the self” in Erica Scourti’s Life in AdWords, where it takes a form that could be read as a neoliberal perversion of Foucault’s “technologies of the self,” in the actual writing of the diary, on which the work is based, as well as in the many Google-generated snippets about self-optimisation – including the memory training, yoga breathing exercises, meditation and improved time-management already mentioned. In all of this, what interests the artist, by her own admission, is above all the aspect of efficiency “as it manifests in rhetoric of self-betterment, and its relation to the neo-

liberal promotion of self-responsibility (if you’re poor, it’s your fault…). Diaries and journal writing – as well as meditation, yoga, therapy, self-help etc. – are often championed in everything from cognitive fitness to management literature as excellent ways of becoming more ‘efficient.’ The underlying belief seems to be that by unloading all the crap that weighs you down, from emotional blockages to unhelpful romantic attachments to an overly-busy mind, you’d get an ‘optimised you.’” Yet the self that is presented in Life in AdWords is not a self that engages us with a joyful or carefree gaze, unencumbered by emotional blockades, happily experimenting with different lifestyles or even simply at one with herself. Instead, what we see is a subject frequently looking exhausted, whose computer-generated profile statements suggest an anxious, neurotic and depressive personality structure.

The Weariness of the Self

The theories proposed by Maurizio Lazzarato and Antonio Negri, who follow Foucault in describing the biopolitical society of the present as a society that no longer operates through force and oppression, but primarily by advocating the enhancement and optimisation of life, offer us a glimpse of the potentially burdensome and destructive impact on the individual that goes hand in hand with new social demands and normative contexts. As already mentioned, Lazzarato points out that it is the individual alone who bears all the risks and responsibilities associated with the promise of self-realisation and emancipation. He describes feelings of guilt, anxiety, frustration, loneliness and bitterness as the ‘passions’ of seemingly sovereign subjects who tend, due to the neoliberal emphasis on self-awareness, to blame themselves for their own troubles and failures instead of seeking the responsibility in the prevailing power structures. Similarly, French sociologist Alain Ehrenberg already noted in the late 1990s in his book The Weariness of the Self that the contemporary subject is bound up in “a normative context that beckons us to become ourselves and to surpass ourselves through action.” According to Ehrenberg, we live in the belief that each of us has, and should have, the possibility of writing our own history – if only we would take the initiative. However, as Ehrenberg points out, the availability of this potential, coupled with the insistence on personal initiative, “accelerates the break-up of permanence and multiplies the supply of reference points, even as it blurs them.” At the same time, the individual is put under increasing pressure to be firmly decisive and active. Any possible inhibitions are quickly dismissed as dysfunctional, or as a “depressive inadequacy.” For the ‘sovereign’ individual of today, the result is a state of exhaustion, indecision or incapacity to act, which, in turn, goes hand in hand with altered definitions, diagnoses and treatments of depression – increasingly coming to be regarded as the leading pathology of our time. Scourti’s Life in AdWords contains remarkably frequent references to depressive feelings, anxiety and sleeplessness – framed by occasional references to the art context and its specific demands on the creative initiative of the individual.

While Ehrenberg regards depression as the face of supposedly sovereign individualism, he sees dependency or addiction as its flip side. Psychotropic and illegal drugs as self-improvement techniques, or even organisations such as “cults whose marketing is centred on personal transformation” can lead, he says, not to self-emancipation, but into “dependency on a master.” An interesting question to examine in this connection would be the extent to which new digital media might be seen as constituting an extension of the techniques used to “improve” the (virtual) self – for example in the form of a computer-generated representation of the self – and whether they converge with Ehrenberg’s descriptions of self-improvement techniques leading to potential dependency as the flip side of sovereign individualism. One relatively topical artwork that suggests this particular issue is Jon Rafman’s Kool-Aid Man in Second Life (2008–2011, fig. 7–8), in which the artist creates an avatar in the form of the Pitcher Man – the mascot of the Kool-Aid powdered drink company – and goes on outings with him in the virtual universe of Second Life.

Fig. 7–8

John Rafman, Kool-Aid Man

in Second Life, screenshots, 2008–2011.

Rafman’s channelling of this advertising symbol – which has achieved iconic status in the USA – also has a bitter aftertaste, given that “drinking the Kool-Aid” has come to be associated in the English-speaking world with references to the Jonestown mass suicide, in which members of the new-age religious cult Peoples Temple killed themselves by drinking a soft drink, similar to Kool-Aid, laced with cyanide. For this reason, “Drinking the Kool-Aid” has since become a commonplace metaphor synonymous with blindly following an ideology. In this respect, Rafman’s appropriation of a marketing symbol as avatar seems to refer not only to the commodification of virtual and frequently idealised representatives of the self, but can also be read as a provocative jibe at the dependency of the sovereign individual on the virtual world or on virtual role-play – an aspect the artist himself mentions when he says, “they [i.e. the other avatars] think that Kool-Aid man is making a joke of everything and suggesting that their attitude to the virtual world or their role-play has become cult-like.”

Erica Scourti’s Life in AdWords and Jon Rafman’s Kool-Aid Man represent two extremes between which the digital representation of the self moves in the present day. Both refer to the dual dilemma of the subject in capitalist society, that is to say, the dilemma between the seemingly authentic, almost real-time screening of the self and the commodified representation of the self, which, in its idealised or deliberately tendentious form, promises something similar to “commodity aesthetics,” to the use value promise of a product. The ‘authentic’ digital capture of the self permits a no-holds-barred input of the self into the capitalist system of commodity circulation by means of new technologies. The deliberately marketable presentation of the self seems to be adapted to the increasing pressures and normative structures of a society in which successful (niche-specific) self-optimisation has become the prerequisite for a successful life – and is thus implied, at least, in corresponding forms of self-representations. There is actually nothing fundamentally new about this kind of self-presentation, in which certain aspects of the self are ‘marketed’ to society. Even in the Renaissance, portraits were used to present a mask or expected societal role, or indeed as a means of deliberately striking a pose to refute that role. This form of self-promotion has merely gained an added dimension, broader popularisation and increased urgency through today’s communications technologies and the emergence of the seemingly sovereign individual in a post-disciplinary society along with the sweeping strategies of exploitation practised by advanced capitalism.

On social networking sites and blogs, these two extremes often come into conflict and are not without an effect on the real self. According to American sociologist Sherry Turkle, merely creating a Facebook profile poses the challenge of numerous decisions regarding the representation of the self – for instance, which hobbies to list, which pictures to post, or which friends to accept. However, this process of self-fashioning, or of composing an identity, leads – especially among adolescents – to an added degree of insecurity in which the controlled, carefully managed, flattering self-portrayal competes with the notion of projecting as authentic an image as possible. “The confusion over who we are and how much we should reveal about our private lives and opinions is on the rise, just as the growing pressure ‘to be yourself’ increasingly conflicts with social conformism,” according to media theoretician and internet activist Geert Lovink. The representation of the self in conformity with conventional notions of authenticity not only clashes with socially normative maxims of self-optimisation but also falls at the hurdle of easily digestible exploitability prescribed by the input requirements of the medium. According to Turkle, social media require that we present ourselves in a simplified way, resulting in a pared-down virtual representation of the self, which, in turn, forces the individual to conform to stereotype, leading, in short, to a constrictive reflection on the subject.

Possible Strategies of Resistance

Self-representation – including, in particular, those representations supported by new communication technologies – thus forms the basis of a real-time feeding of the subject into capitalist market mechanisms with all their empowering and exploitative strategies. On the other hand, however, they also often reveal themselves to be the result of neoliberal maxims of self-optimisation which encourage the subject to adopt an ideal self-profile that is socially standardised, consumer-friendly and marketable – the Western stereotype of the successful individual – while at the same time offloading the sole responsibility for happiness onto the individual. Strategies that aim at emancipating and distancing the subject from the current exploitative mechanisms of an accelerating and exponential consumption of the earth’s resources and which free them of the neoliberal pressure to be pro-active and market themselves, therefore, need to take a two-pronged approach: by tackling the self-representation of the subject – the representation of identities – and also by tackling the fundamental concept of subjectivity within the overall social and ecological framework. With regard to the self-representation of the subject, the most important aspect that needs to be countered is the stereotypical portrayal that occurs when digital information about an individual is translated into a definitive user profile (and the targeted advertising this elicits) and the abbreviated, tendentious and ‘marketable’ self-portrayal that occurs on social media sites. After all, stereotyping as “an arrested, fixated form of representation,” which has long been recognised by such post-colonial theoreticians as Homi Bhabha and Stuart Hall with regard to the representation of the Other, prohibits the all-important “play of difference” and ongoing negotiations that are a necessary factor in constantly re-calibrating cultures and identities and challenging existing power structures. One possible strategy, as Stuart Hall suggests, would be “to make the stereotypes work against themselves,” without actually avoiding them, but instead potentially deconstructing them in a humorous way that would undermine them or contest them from within. That is pretty much what happens in Erica Scourti’s Life in AdWords, which serves up a well-measured dose of the Gmail version of her self and, in doing so, wittily reveals the stereotyping indulged in by both herself and others, while undermining it in a parodistic way.

Post-colonial and anti-colonial theories have also set important parameters for a new concept of subjectivity, and for “a vision of the subject that is ‘worthy of the present.’” Taking a stance against the dominant humanistic ideal of the white male who, in overestimating his identity, legitimises the exploitation of colonised peoples and the Other, such theories counteract the perpetuation of rigid identities and one-sided Western normative structures with concepts of hybridisation and creolisation. The conclusion that all cultures are mixed and hybrid and that cultures, languages and ethnicities are becoming increasingly interwoven, also due to recent global migration movements, further supports the concept of the subject with multiple affiliations and “relational identities.” Current theoreticians of a new materialism such as Manuel De Landa and Rosi Braidotti have liberated this notion of the non-unitary subject, shaped by encounters and relationships, from its purely cultural context and have placed it within the context of an overall nature/culture framework of all things human and non-human. In her materialist post-humanist approach, Braidotti has proclaimed the concept of the “nomadic” or “relational subject,” being aware of a direct connection with multiple others within a vibrant network of complex interrelations and capable of exploring the potential of its Becoming through diverse encounters with Otherness. In such a non-profit-driven experiment with relationally determined virtual possibilities of subjectivity – whereby virtual is meant here in the Deleuzian sense of manifold ideal potentiality – she recognises a necessary qualitative step towards escaping the “neutralization of difference” and the “regime of commodification” that prevail in advanced capitalism, providing the possibility of forging a new normative frame of reference for the post-human subject. In this, Braidotti acknowledges the major role played by technological media. In her view, the merging and reciprocal interaction between bodies and technical Others – as evidenced, for example, in the current exterritorialisation and electronic expansion of the human nervous system by means of cutting-edge information and communications technologies – promote an all-encompassing machine vitality, a process of “becoming-machine” in the sense of Deleuze and Guattari. This, however, also leads, she posits, to a “privileged bond with multiple others” as well as to a merging with our own “technologically mediated planetary environment.” According to this positive view, technologies no longer serve as vehicles of a ruthless commodification of the self, nor as prosthetics or communicative and visual aids to a biopolitical, neoliberal self-optimisation of the individual. Instead, in their interaction and merging with responsible organisms – to loosely adopt Donna Haraway’s maxim of “affinity, not identity” – they form a transversal and boundary-crossing amalgam. Notwithstanding, the question still remains as to what it actually means specifically to be a relational subject and to grasp technologies, including the new communications technologies, as hybridising and interactive components of a subjectivity that is resistant to neoliberal strategies of exploitation. It is a question to be posed anew on a daily basis, and an issue to be realised – through appropriate actions as well as through our own non-fixed representations of the self.